~~* The Singing Falls Stream Restoration Project *~~

ϕ

ϕ

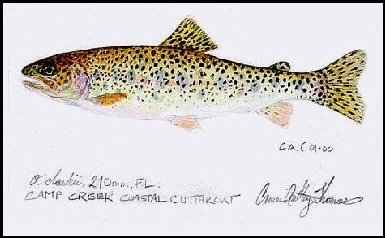

The Oregon Coast Cutthroat Trout: Oncorhynchus clarki

The information below is a presentation from the Corps of Engineers permit application for the Joe Hall restoration project and a presentation by OSU Sea Grant program on this particular fish found in Joe Hall Creek. Yearly there are usually several “Cutties” that take up residence in the pools at the base of Singing Falls during the seasonal summer drought. If you take the time to view the Cutthroat area usage map you see that the South Umpqua Cutthroat Trout has the greatest amount of habitat usage in the area. In spite of this the fish is loosing ground in its battle to survive.

On several excursions to the upper reaches of Joe Hall Creek I have found the Coastal Cutthroat trout all the way up to the main fish barrier on the stream located at a 30 foot high waterfall about a mile up stream from our ranch. These tenacious fish hold over in some very small perennial pools found among massive boulder laden reaches of the stream. The USFS fish biologists believe all three life history types live in Joe Hall Creek. Oddly enough I have found trout up above one of the main natural fish barriers on Joe Hall Creek. It is surmised that Native Americans placed them there years ago. The variety of Cutthroat Trout associated with our watershed is the South Umpqua Coastal Cutthroat Trout.

From the Corps of Engineers Permit for the restoration project

“At least three life history forms occur within the Umpqua basin and all three may occur within the project area. The three life history strategies include anadromous, fluvial and resident. Although behavior, freshwater residency, habitat use, and other factors may be described differently for these life histories, enough common requirements make it possible to assess the effects of an action on all three strategies. Low to moderate gradient streams and rivers are commonly used for spawning, rearing and residency. Water temperature requirements in common use are described in NMFS (1996), which includes preferred temperature requirements of 10 °C to 13.9 °C (considered Properly Functioning watersheds). Complex stream channels may be described as a stream channel with a diversity of pool and riffle habitat that includes physical structure, such as wood or boulders; connection to floodplains and low velocity side channels; a diversity of water.”

COASTAL CUTTHROAT TROUT: LIFE IN THE WATERSHED

Coastal cutthroat trout is one of three cutthroat subspecies found in Oregon. The coastal subspecies, which is closely related to steelhead/rainbow trout and Pacific salmon, displays the most diverse and flexible life history of any of the Oregon salmonids. Coastal cutthroat can be found in streams and rivers from the Eel River in northern California to Prince William Sound in Alaska.

Adult cutthroat trout are distinguished from steelhead and Pacific salmon by the length of the upper jaw bone, which extends well behind the eye, and by the presence of two red-orange slashes below the lower jaw. (These slashes may be absent in silvery, sea-run cutthroat.) Juvenile cutthroat trout are identified by long, numerous, black spots on the tail fin.

In Oregon, coastal cutthroat use various life history strategies to occupy a variety of ecosystems in most coastal and lower Columbia River streams. This distribution closely follows the coastal rain forest belt. Mature fish may range from 6 inches, in populations that remain in small headwater streams throughout the life cycle, to 20 inches, in populations that migrate to and from the ocean.

Current abundance is not known, but many scientists believe that populations have declined substantially since the 1950s and 1960s. The federal government listed the coastal cutthroat trout as endangered throughout the Umpqua River basin below natural barriers in August 1996, and the state government considers populations in the lower Columbia to be sensitive. The lack of good population information for the remaining coastal streams and rivers, along with the cutthroat's demonstrated sensitivity to habitat disturbance, makes vigilance the rule.

Efforts to restore and conserve cutthroat trout must focus on improving habitat in the watersheds where they live. At the same time, we must address other factors that threaten cutthroat, such as harvest and hatchery effects.

Coastal residents have a critical role to play in improving fish habitat in watersheds. Improving watersheds will prevent extinction of species and benefits individuals and communities by enhancing water quality and quantity.

This publication is designed to help you understand how, where, and when cutthroat trout live in watersheds and the role you can play in conserving and restoring this natural heritage.

The Flexible, yet Fragile, Existence of Cutthroat Trout

Because it is a master at solving the problems of living in many diverse environments, the coastal cutthroat trout has been likened to the canary in the coal mine--if its populations are declining, what does that say about our coastal environment?

Although cutthroat trout share many characteristics with their cousins the Pacific salmon, they differ (along with steelhead trout) in that some adult cutthroat survive spawning to reproduce again.

Coastal cutthroats come in all sizes and spots. Scientists typecast them into four major categories: resident, fluvial, adfluvial, and anadromous.

RESIDENT cutthroats, darker with prominent spots, dominate most of the headwater tributaries and small coastal streams in Oregon. These environments are often closed to larger salmon and trout by barriers, but the small cutthroats found there thrive, rarely venturing far from the site in which they hatched.

FLUVIAL cutthroats are found in larger river systems throughout the coast. These fish remain in the rivers for most of their adult lives, leaving only briefly to migrate into smaller tributaries to spawn or to seek refuge in winter months.

ADFLUVIAL populations, like the other cutthroats, spawn in tributaries; however, juveniles and post-reproductive adults migrate to coastal lakes rather than the ocean or large rivers. These lakes may be either isolated or connected to the ocean.

ANADROMOUS (or sea-run) populations of cutthroat migrate as juveniles to estuaries and the ocean in the spring, like their salmon and steelhead cousins. However, the fish stay in the estuaries or nearshore waters, rarely migrating more than 40 miles offshore, and usually return to freshwater later that same year in summer or fall.

These returnees, silvery and lacking spots, may either spawn in streams that first winter or spring or return to the sea for yet another cycle of growing and maturing.

This flexibility in life patterns means that cutthroats use all parts of coastal watersheds. Yet cutthroats are the least aggressive of the salmon and trout found in these waters and are often pushed to marginal habitat by more aggressive coho salmon and steelhead trout. This means that cutthroats teeter on the brink, making them critically dependent on functioning watersheds to provide refuge.

Watersheds are the circulatory system of the land, draining ridgetops through streams and then rivers and finally coming to a confluence in a lake or the ocean. (Evaporation from the ocean falls on the highlands in the form of rain or snow to complete the circuit.) Fire, landslides, erosion, and flooding occur naturally in watersheds, helping to create and maintain the conditions and habitats in which cutthroat and other species have evolved.

For example, woody debris and boulders create structural complexity in stream pools, which in turn provide cutthroat trout shelter from their aggressive coho and steelhead cousins.

The creation of this habitat relies on periodic disturbances that occur naturally within a watershed. Human activities sometimes modify the watershed drastically or frequently, exaggerating the natural disturbances to a stream and compromising fish survival.

Functioning watersheds are important to us and to fish. We've come to depend on watersheds for timber, suitable land for farming and grazing, and drinking and irrigation water. The lands that people manage provide large wood, boulders, gravel, shade, and food that build healthy stream habitats for trout and salmon. It's a fact: we share the watershed, so we must care for the watershed. We, and other living things, depend on it.

The “RESIDENT” type of the “Cutthroat” trout.

Life history

Resident cutthroats grow, mature, and spawn often very close to the location from which they hatched. Adult cutthroat trout may be as small as 6 inches long, but most mature at a length between 10 and 20 inches.

Fluvial and adfluvial cutthroats migrate to spawning streams in the spring, usually to the streams in which they hatched (natal streams), and spawn in spring or summer in small streams.

Sea-run cutthroats migrate into freshwater in late summer to late fall, usually to their natal streams, and spawn from late winter to spring. The adults migrate back to the ocean shortly after spawning.

The eggs hatch in summer, the precise time depending on water temperature.

Resident cutthroat fry emerge in spring or summer and remain in their natal streams.

Fluvial and adfluvial cutthroat fry also emerge in spring or summer and may remain in their natal streams or migrate (usually the following spring) to other streams, rivers, or lakes.

Sea-run cutthroat fry migrate to lower reaches of streams after emerging from the gravel in spring or summer. As early as the following spring, but more often two to four springs later, juvenile cutthroat trout migrate to estuaries and the ocean as seawater-adapted “smolts.”

For successful production, juvenile cutthroat trout that live at the edges of streams or in backwater areas depend on the presence of streambank vegetation and abundant instream structure created by logs and root wads.

4 In the marine environment, cutthroat trout tend to grow about an inch every month, feeding on a variety of small crustaceans and fish. Their residency in seawater is brief-- usually only a few months--and they tend to stay close to the freshwater streams and rivers from which they came. The fish return to freshwater later the same year in autumn to spawn or to spend another year growing and developing before undertaking another seaward migration.

You Can Help Salmon

Oregon's coastal cutthroat trout--and coho, steelhead, and chinook-- can be saved! Land owners and managers play an important part in this effort. Whether your land covers hundreds of acres or a residential lot in town, you can help. The first way is by simply being aware of your place in the watershed and of your local fish runs. The second way is to help provide the habitat conditions the fish need. Here are a few helpful tips for different kinds of landowners.

Forest Operations

- Protect streamside trees and other vegetation at least consistent with the Oregon Forest Practices Act requirements.

- Leave good natural features, such as a beaver pond or natural side channel, alone. These are important rearing areas for fish.

- Check areas where your roads cross streams. If your culverts have a drop or are above the stream channel, they could be barriers to fish passage. Consider redesigning problem culverts or replacing them completely with a bridge structure.

Agricultural Businesses

- Create streamside (riparian) pastures that can be managed for grazing during times when livestock will prefer pasture grasses over riparian trees and shrubs. Provide a trough or watering tank away from the stream.

- Plant willows, cottonwood, poplar, or other shrubs and trees along your waterways. They help stabilize the banks, filter out sediments from runoff, and provide cooling shade.

- If riparian pastures are not viable options for your operation, consider using fencing to keep animals away from the water's edge.

- Protect wetlands, rivers, and estuaries through careful animal waste management and from the effects of poor fertilizer or herbicide application.

Land Developers, Homeowners, Businesses

- While state and federal law may allow filling wetlands or estuaries (with the proper review and permits), loss of such habitat can harm fish. Consider options that preserve these habitats.

- Construction can cause serious sediment problems, even well away from a waterway, if storm-water runoff is not properly contained. Although smaller operations may not need permits, they still can have significant impacts. Check with the state Department of Environmental Quality or local construction companies about responsible runoff management at your site.

- If possible, homeowners and businesses should connect to a sewage treatment and disposal facility. Poorly performing septic tanks can contaminate groundwater and nearby streams, lakes, and bays. If you must use a septic tank, be certain it is properly designed, located, and maintained.

- Dispose of household chemicals such as used motor oil, antifreeze, pesticides, and paints at approved collection facilities in your area.

Production: Cooper Publishing

© 1999 by Oregon Sea Grant, Oregon State University

This publication may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety for noncommercial purposes.

ORESU-G-99-011

top

stream index