~~* The Singing Falls Stream Restoration Project *~~

ϕ

ϕ

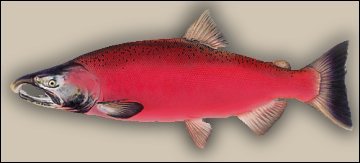

The Oregon Coastal Coho Salmon: Oncorhynchus kisutch

The information below is a presentation from the Corps of Engineers permit application for the Joe Hall restoration project containing information on the Coho Salmon found at Singing Falls and by OSU Sea Grant program. At one time Coho salmon appeared in Joe Hall Creek and Alexandra Creek in great abundance. The old timers in the area called them the “Thanksgiving Fish” because they annually appeared in our region of the Umpqua Basin during the last half of November. Be sure to see the mpgs and jpgs of our first few Salmon runs here at Singing Falls

A map illustrating the extent of the Coho Salmon range in the region surrounding our area can be found here.

This male coho salmon caught my eye during the 2005-2006 rainy season. I was counting salmon nests (“redds,”) in Joe Hall creek. I paused where Alexandra Creek meets it when out of the corner of my eye a flash of ruby red turned my head.

Buck Coho heading toward Singing Falls

From the Corps of Engineers Permit for our restoration project

ODF&W estimates that there are 340 miles of coho habitat occurring in the South Umpqua basin. Most South Umpqua coho spawn and rear in the Cow Creek subbasin or in the lower South Umpqua tribs, which are downstream from the Forest. Important coho streams on the Tiller district of Umpqua National Forest include Dumont, Deadman, Elk, Jackson, and Beaver Creeks. Of these locations, Beaver and Dumont Creeks have had the highest numbers of coho spawners observed (15-30 spawners per mile) since the mid 1980s, followed by Joe Hall and Francis Creeks.

Coho temperature requirements are similar to steelhead. Pool habitat, especially those associated with woody debris complexes provide resting areas and cover. Poor quality rearing habitat for juvenile coho is believed to currently be a limiting factor to coho production in the South Umpqua River. Juvenile coho prefer to reside in pools associated with wood debris accumulations. During winter they also prefer side channels, and interstitial spaces between cobbles and boulders.

The Oregon Sea Grant

COHO SALMON: LIFE IN THE WATERSHED

Coho salmon have been the most important variety of salmon caught commercially in Oregon. Until recently, coho were also the most common variety in most coastal streams. Based on records from salmon canneries, coho in Oregon north of Cape Blanco (near Port Orford) numbered about 1,500,000 adults annually 100 years ago.

During recent years, the annual production of wild coastal coho in Oregon has been dramatically less, around 50,000 to 80,000 fish--a 90 percent decline. Given this decline, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) considered listing two groups of coastal coho in Oregon as threatened under the Federal Endangered Species Act. In April 1997 the agency decided to list a population of coho that spans the Oregon-California border, from Cape Blanco south to Punta Gorda. Meanwhile NMFS placed the population north of Cape Blanco to the Columbia River on a “candidate list” and agreed to let Oregon attempt to recover Oregon coho according to a plan developed by state agencies, working with local groups.(As of 2007 Coho Salmon {Oncorhynchus kisutch} have been listed in Oregon.)

The goal of the Oregon Plan is not merely to prevent the extinction of coho salmon in the coastal region, but to restore salmon populations. Efforts to restore salmon must focus on improving the fish's habitat in the watersheds it lives in, along with addressing other factors of its decline, such as harvest and hatchery effects on the species.

Male Coho in its fresh water spawning phase illustrating its brilliant red color.

Coastal residents have a critical role to play in improving fish habitat in watersheds. Improving watersheds can not only help prevent the extinction of species, but also provide benefits to individuals and communities in terms of enhanced water quality and quantity.

This publication is designed to help readers understand the fundamentally important how, when, and where coho salmon live in watersheds and what people can do to help.

The Oregon coast's most important producers of wild coho salmon are the Nehalem, Nestucca, Siletz, Alsea, Siuslaw, Umpqua, Coos, Coquille, and Rogue Rivers; Tillamook Bay tributaries; and Siltcoos, Tahkenitch, and Tenmile Lakes (on the central coast).]

A watershed is the land area onto which rain or snow falls and is stored and from which this water drains over time. The drainage occurs through a river to a single point, such as a lake or the ocean. The boundaries of a watershed are the ridgelines that separate it from neighboring watersheds.

From the ridgetops to the water body, the watershed drains all land areas. These areas are connected. We know that actions and consequences are connected in a watershed: what happens upslope and upstream eventually comes down.

Functioning watersheds are important to us and to fish. We've come to depend on them for timber, for suitable land for farming and grazing, and for drinking and irrigation water. The land areas that people manage provide large wood, boulders, gravel, shade, and food that build healthy stream habitats for coho salmon. It's a fact: we all live in a watershed--not only people, but the salmon and other animal and plant species, too.

No single picture can convey the understanding that a stream is an ever-changing ecosystem that reflects the condition of the watershed around it. The stream and riparian (streamside) areas are especially dynamic, shaped by such disturbances as fire and windthrow, channel erosion, peak flows, floods, and debris flows. Such natural disturbances are a normal part of a stream's existence and help create the conditions and habitats that salmon and other species have adapted to over evolutionary time. However, human activities that modify the watershed and stream channel can exaggerate the effects of natural disturbances, with detrimental results.

This female Coho is called a “SILVER” because of the silvery characteristic of Coho Salmon while they roam the Pacific Ocean. A unique phase of their lifecycle.

Life history

1. Adult coho migrate into freshwater in the fall to spawn, usually to the stream they themselves were born in. Spawners are typically three years old and weigh 4 to 12 pounds.

Spawning usually occurs from mid-November through February.

Females create nests in the gravel, called “redds,” where they deposit their eggs. The gravel needs to be clean and range in size from a pea to an orange.

Coho prefer to spawn and rear in small, relatively flat streams.

2. The eggs hatch in about 35 to 50 days. Juveniles emerge as “fry” in the spring and spend one summer and one winter in freshwater.

Because they are small, they seek wetlands, off-channel ponds, and slackwater areas in pools to survive swift currents during the winter.

Cool water is required for rearing (53–58°F is preferred; 68°F is maximum).

After the first summer in the ocean, a small proportion of the males become sexually mature and return to spawn as “jacks.”

3. In the spring, about a year after their emergence, juveniles migrate to the ocean as silvery “smolts.”

Smolts are four to five inches long and can survive in saltwater. The smolts grow rapidly in the ocean.

Little is known about where coho from Oregon coastal streams migrate.

4. Coho remaining at sea over the second winter feed voraciously during the next spring and summer.

Adults grow to about 23 to 33 inches in length. In the fall, coho that escape predators, fishers, and natural calamities return to their home streams or neighboring streams.

After spawning, coho die and, if left to decay in the rivers, contribute nutrients to support the next generation of coho.

Habitat complexity, primarily in the form of large and small wood, is an important element of productive coho salmon streams.

This image serves the purpose of illustrating the size of these fish when they appear in Joe Hall Creek at Singing Falls.

You Can Help Salmon

Oregon's coastal coho--and chinook, steelhead, and cutthroat trout--can be saved! Land owners and managers play an important part in this effort. Whether your land covers hundreds of acres or a residential lot in town, you can help. The first way is by simply being aware of your place in the watershed and of your local fish runs. The second way is to help provide the habitat conditions the fish need. Here are a few helpful tips for different kinds of landowners.

Forest Operations

- Protect streamside trees and other vegetation at least consistent with the Oregon Forest Practices Act requirements.

- Leave good natural features, such as a beaver pond or natural side channel, alone. These are important rearing areas for fish.

- Check areas where your roads cross streams. If your culverts have a drop or are above the stream channel, they could be barriers to fish passage. Consider redesigning problem culverts or replacing them completely with a bridge structure.

Agricultural Businesses

- Create streamside (riparian) pastures that can be managed for grazing during times when livestock will prefer pasture grasses over riparian trees and shrubs. Provide a trough or watering tank away from the stream.

- Plant willows, cottonwood, poplar, or other shrubs and trees along your water ways. They help stabilize the banks, filter out sediments from runoff, and provide cooling shade.

- If riparian pastures are not viable options for your operation, consider using fencing to keep animals away from the water's edge.

- Protect wetlands, rivers, and estuaries through careful animal waste management and from the effects of poor fertilizer or herbicide application.

Land Developers, Homeowners, Businesses

- While state and federal law may allow filling wetlands or estuaries (with the proper review and permits), loss of such habitat can harm fish. Consider options that preserve these habitats.

- Construction can cause serious sediment problems, even well away from a waterway if storm-water runoff is not properly contained. Although smaller operations may not need permits, they still can have significant impacts. Check with the state Department of Environmental Quality or local construction companies about responsible runoff management at your site.

- If possible, homeowners and businesses should connect to a sewage treatment and disposal facility. Poorly performing septic tanks can contaminate groundwater and nearby streams, lakes, and bays. If you must use a septic tank, be certain it is properly designed, located, and maintained.

- Dispose of household chemicals such as used motor oil, antifreeze, pesticides, and paints at approved collection facilities in your area.

The elders of our village say that this is the way it once was during the November Coho Salmon Runs. By December the stream was bright red due to the color changes of the Coho.

Production: Cooper Publishing

© 1999 by Oregon Sea Grant, Oregon State University

This publication may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety for noncommercial purposes ORESU-G-99-013

top

stream index